- Home

- H. P. Lovecraft

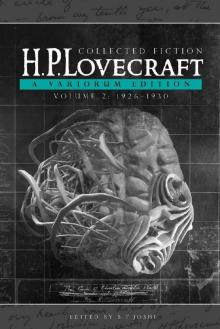

Collected Fiction Volume 2 (1926-1930): A Variorum Edition

Collected Fiction Volume 2 (1926-1930): A Variorum Edition Read online

Collected Fiction: 1926–1930

H. P. LOVECRAFT

Collected Fiction

A VARIORUM EDITION

VOLUME 2: 1926–1930

Edited by S. T. Joshi

Hippocampus Press

—————————

New York

Copyright © 2016 by Hippocampus Press.

Selection, editing, and editorial matter copyright © 2015 by S. T. Joshi.

Lovecraft material used by permission of the Estate of H. P. Lovecraft; Lovecraft Properties, LLC.

First Electronic Edition.

Published by Hippocampus Press

P.O. Box 641, New York, NY 10156.

http://www.hippocampuspress.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

Cover design and cover artwork by Fergal Fitzpatrick. For the cover of volume two, Mr. Fitzpatrick has used abstract truth and scientific logic as his conceptual departure.

“I should describe mine own nature as tripartite, my interests consisting of three parallel and dissociated groups—(a) Love of the strange and the fantastic. (b) Love of the abstract truth and of scientific logick. (c) Love of the ancient and the permanent. Sundry combinations of these three strains will probably account for all my odd tastes and eccentricities.”

—H. P. Lovecraft to Rheinhart Kleiner (7 March 1920)

Portrait of H. P. Lovecraft, c 1930.

Photo of S. T. Joshi by Emily Marija Kurmis.

Hippocampus Press logo designed by Anastasia Damianakos.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

ISBN: 978-1-61498-169-5 Kindle

ISBN: 978-1-61498-170-1 Epub

Contents

Introduction

Cool Air

The Call of Cthulhu

Pickman’s Model

The Silver Key

The Strange High House in the Mist

The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath

The Case of Charles Dexter Ward

The Colour out of Space

The Descendant

History of the “Necronomicon”

Ibid

The Dunwich Horror

The Whisperer in Darkness

Introduction

The stories in this volume constitute, on the whole, a body of work that first appeared in pulp magazines without initial publication in amateur journals. As a result, Lovecraft did not have much of an opportunity to revise these texts, as he had done for many of the stories that had first appeared in amateur periodicals. Two exceptions to this rule are “Pickman’s Model” (which was slightly revised for its second appearance in Weird Tales) and “The Colour out of Space” (which was revised for a proposed book publication by F. Lee Baldwin that never eventuated).

Lovecraft’s two short novels, The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath and The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, lay unpublished at the time of his death. He made no effort to prepare these texts for publication, although R. H. Barlow prepared partial typescripts of them (both of which contain slight revisions and corrections by Lovecraft). It would, however, be inaccurate to say that these stories are mere first drafts; the extent to which Lovecraft revised them in the course of composition bespeaks considerable care in matters of structure and style. Dream-Quest is slightly less revised than Ward, true to its nature as a “practice” novel (SL 2.95).

The two humorous squibs, “History of the ‘Necronomicon’” and “Ibid,” also remained unpublished until after Lovecraft’s death, as did the fragment “The Descendant.” “Ibid” is the only work in this volume for which a manuscript has not come to light. It was presumably sent to Maurice W. Moe, and its whereabouts among Moe’s effects are unknown. For “The Colour out of Space,” we do not have Lovecraft’s original A.Ms. or T.Ms., but a T.Ms. presumably prepared by Baldwin, revised by the author.

Of the texts in this volume, “The Call of Cthulhu” and the two short novels were very poorly printed by Arkham House, because it unwisely chose (in the case of “The Call of Cthulhu”) to follow the poor Weird Tales text, and (in the case of the novels) because whoever transcribed the texts exhibited a poor ability to read Lovecraft’s handwriting. Such major stories as “The Colour out of Space,” “The Dunwich Horror,” and “The Whisperer in Darkness” were well printed by Arkham House because it followed Lovecraft’s T.Ms.

The dream-account later titled “The Very Old Folk” was written in late 1927, embodied in a letter to Donald Wandrei. It appears in the Appendix to Volume 3.

Abbreviations used in the notes are as follows:

A.Ms. autograph manuscript

JHL John Hay Library, Brown University (Providence, RI)

om. omitted

SL Selected Letters (1965–76; 5 vols.)

T.Ms. typed manuscript

—S. T. JOSHI

Collected Fiction: 1926–1930

Cool Air

You ask me to explain why I am afraid of a draught[1] of cool air; why I shiver more than others upon entering a cold room, and seem nauseated and repelled when the chill of evening creeps through the heat of a mild autumn day. There are those who say I respond to cold as others do to a bad odour,[2] and I am the last to deny the impression. What I will do is to relate the most horrible circumstance[3] I ever encountered, and leave it to you to judge whether or not this forms a suitable explanation of my peculiarity.

It is a mistake to fancy that horror is associated inextricably with darkness, silence, and solitude. I found it in the glare of mid-afternoon,[4] in the clangour of a[5] metropolis, and in the teeming midst of a shabby and commonplace rooming-house with a prosaic landlady and two stalwart men by my side. In the spring of 1923 I had secured some dreary and unprofitable magazine work in the city of New York; and being unable to pay any substantial rent, began drifting from one cheap boarding establishment to another in search of a room which might combine the qualities of decent cleanliness, endurable furnishings, and very reasonable price. It soon developed that I had only a choice between different evils, but after a time I came upon a house in West Fourteenth Street which disgusted me much less than the others I had sampled.

The place was a four-story mansion of brownstone, dating apparently from the late ’forties,[6] and fitted with woodwork and marble whose stained and sullied splendor[7] argued a descent from high levels of tasteful opulence. In the rooms, large and lofty, and decorated with impossible paper and ridiculously ornate stucco cornices, there lingered a depressing mustiness and hint of obscure cookery; but the floors were clean, the linen tolerably regular,[8] and the hot water not too often cold or turned off, so that I came to regard it as at least a bearable place to hibernate till[9] one might really live again. The landlady, a slatternly, almost bearded Spanish woman named Herrero, did not annoy me with gossip or with criticisms[10] of the late-burning electric light in my third-floor [11] front hall room; and my fellow-lodgers were as quiet and uncommunicative as one might desire, being mostly Spaniards a little above the coarsest and crudest grade. Only the din of street cars in the thoroughfare below proved a serious annoyance.

I had been there about three weeks when the first odd incident occurred. One evening at about eight I heard a spattering on the floor and became suddenly aware that I had been smelling the pungent odour [12] of ammonia for some time. Looking about, I saw that the ceiling was wet and dripping; the soaking apparently proceeding from a corner on the side toward the street. Anxious to stop the matter at its source, I hastened to the basement to tell the landlady; and was assured by her

that the trouble would quickly be set right.

“Doctair Muñoz,” she cried as she rushed upstairs ahead of me, “he have speel hees chemicals. He ees too seeck for doctair heemself—seecker and seecker all the time—but he weel not have no othair for help. He ees vairy queer in hees seeckness—all day he take funnee-smelling baths, and he cannot get excite or warm. All hees own housework he do—hees leetle room are full of bottles and machines, and he do not work as doctair. But [13] he was great once—my fathair in Barcelona have hear of heem—and only joost now he feex a[14] arm of the plumber that get hurt of sudden. He nevair go out, only on roof, and my boy Esteban[15] he breeng heem hees food and laundry and mediceens and chemicals. My Gawd,[16] the sal-ammoniac [17] that man use for [18] keep heem cool!”

Mrs. Herrero disappeared up the staircase to the fourth floor, and I returned to my room. The ammonia ceased to drip, and as I cleaned up what had spilled and opened the window for air, I heard the landlady’s heavy footsteps above me. Dr. Muñoz I had never heard, save for certain sounds as of some gasoline-driven mechanism; since his step was soft and gentle. I wondered for a moment what the strange affliction of this man might be, and whether his obstinate refusal of outside aid were not the result of a rather baseless eccentricity. There is, I reflected tritely, an infinite deal of pathos in the state of an eminent person who has come down in the world.

I might never have known Dr. Muñoz had it not been for the heart attack that suddenly seized me one forenoon as I sat writing in my room. Physicians had told me of the danger of those spells, and I knew there was no time to be lost; so [19] remembering what the landlady had said about the invalid’s help of the injured workman, I dragged myself upstairs and knocked feebly at the door above mine. My knock was answered in good English by a curious voice some distance to the right, asking my name and business; and these things being stated, there came an opening of the door next to the one I had sought.

A rush of cool air greeted me; and though the day was one of the hottest of late June, I shivered as I crossed the threshold into a large apartment whose rich and tasteful decoration surprised me in this nest of squalor and seediness. A folding couch now filled its diurnal role of sofa, and the mahogany furniture, sumptuous hangings, old paintings, and mellow bookshelves all bespoke a gentleman’s study rather than a boarding-house bedroom. I now saw that the hall room above mine—the “leetle room” of bottles and machines which Mrs. Herrero had mentioned—was merely the laboratory of the doctor; and that his main living quarters lay in the spacious adjoining room whose convenient alcoves and large contiguous bathroom permitted him to hide all dressers and obtrusive utilitarian devices. Dr. Muñoz, most certainly, was a man of birth, cultivation, and discrimination.

The figure before me was short but exquisitely proportioned, and clad in somewhat formal dress of perfect cut and fit.[20] A high-bred face of masterful though not arrogant expression was adorned by a short iron-grey full beard, and an old-fashioned pince-nez shielded the full, dark eyes and surmounted an aquiline nose which gave a Moorish touch to a physiognomy otherwise dominantly Celtiberian. Thick, well-trimmed hair that argued the punctual calls of a barber was parted gracefully above a high forehead; and the whole picture was one of striking intelligence and superior blood and breeding.

Nevertheless, as I saw Dr. Muñoz in that blast of cool air, I felt a repugnance which nothing in his aspect could justify. Only his lividly inclined complexion and coldness of touch could have afforded a physical basis for this [21] feeling, and even these things should have been excusable considering the man’s known invalidism. It might, too, have been the singular cold that alienated me; for such chilliness was abnormal on so hot a day, and the abnormal always excites aversion, distrust, and fear.

But repugnance was soon forgotten in admiration, for the strange physician’s extreme skill at once became manifest despite the ice-coldness and shakiness of his bloodless-looking hands. He clearly understood my needs at a glance, and ministered to them with a master’s deftness; the while reassuring me in a finely modulated though oddly hollow and timbreless voice that he was the bitterest of sworn enemies to death, and had sunk his fortune and lost all his friends in a lifetime [22] of bizarre experiment devoted to its bafflement and extirpation. Something of the benevolent fanatic seemed to reside in him, and he rambled on almost garrulously as he sounded my chest and mixed a suitable draught [23] of drugs fetched from the smaller laboratory room. Evidently he found the society of a well-born man a rare novelty in this dingy environment, and was moved to unaccustomed speech as memories of better days surged over him.

His voice, if queer, was at least soothing; and I could not even perceive that he breathed as the fluent sentences rolled urbanely out. He sought to distract my mind from my own seizure by speaking of his theories and experiments; and I remember his tactfully consoling me about my weak heart by insisting that will and consciousness are stronger than organic life itself, so that if a bodily frame be but originally healthy and carefully preserved, it may through a scientific enhancement of these qualities retain a kind of nervous animation despite the most serious impairments, defects, or even absences in the battery of specific organs. He might, he half-jestingly [24] said, some day teach me to live—or at least to possess some kind of conscious existence—without any heart at all! For his part, he was afflicted with a complication of maladies requiring a very exact regimen which included constant cold. Any marked rise in temperature might, if prolonged, affect him fatally; and the frigidity of his habitation—some 55 or 56 [25] degrees Fahrenheit—was maintained by an absorption system of ammonia cooling, the gasoline engine of whose pumps I had often heard in my own room below.

Relieved of my seizure in a marvellously short while, I left the shivery place a disciple and devotee of the gifted recluse. After that I paid him frequent overcoated calls; listening while he told of secret researches and almost ghastly results, and trembling a bit when I examined the unconventional and astonishingly ancient volumes on his shelves. I was eventually, I may add, almost cured of my disease for all time by his skilful ministrations. It seems that he did not scorn the incantations of the mediaevalists,[26] since he believed these cryptic formulae to contain rare psychological stimuli which might conceivably have singular effects on the substance of a nervous system from which organic pulsations had fled. I was touched by his account of the aged Dr. Torres of Valencia, who had shared his earlier experiments and nursed him through the great illness of eighteen years before, whence his present disorders proceeded. No sooner had the venerable practitioner saved his colleague than he himself succumbed to the grim enemy he had fought. Perhaps the strain had been too great; for Dr. Muñoz made it whisperingly clear—though not in detail—that the methods of healing had been most extraordinary, involving scenes and processes not welcomed by elderly and conservative Galens.

As the weeks passed, I observed with regret that my new friend was indeed slowly but unmistakably losing ground physically, as Mrs. Herrero had suggested. The livid aspect of his countenance was intensified, his voice became more hollow and indistinct, his muscular motions were less perfectly coördinated, and his mind and will displayed less resilience and initiative. Of this sad change he seemed by no means unaware, and little by little his expression and conversation both took on a gruesome irony which restored in me something of the subtle repulsion I had originally felt.[27]

He developed strange caprices, acquiring a fondness for exotic spices and Egyptian incense till[28] his room smelled like the vault of a sepulchred Pharaoh in the Valley of Kings. At the same time[29] his demands for cold air increased, and with my aid he amplified the ammonia piping of his room and modified the pumps and feed of his refrigerating machine till he could keep the temperature as low as 34° or 40°,[30] and finally even 28°;[31] the bathroom and laboratory, of course, being less chilled, in order that water might not freeze, and that chemical processes might not be impeded. The tenant adjoining him complained of the icy air from around th

e connecting door,[32] so I helped him fit heavy hangings to obviate the difficulty. A kind of growing horror, of outré and morbid cast, seemed to possess him. He talked of death incessantly, but laughed hollowly when such things as burial or funeral arrangements were gently suggested.

All in all, he became a disconcerting and even gruesome companion; yet in my gratitude for his healing [33] I could not well abandon him to the strangers around him, and was careful to dust his room and attend to his needs each day, muffled in a heavy ulster which I bought especially for the purpose. I likewise did much of his shopping, and gasped in bafflement at some of the chemicals he ordered from druggists and laboratory supply houses.

An increasing and unexplained atmosphere of panic seemed to rise around his apartment. The whole house, as I have said, had a musty odour;[34] but the smell in his room was worse—[35]and in spite of all the spices and incense, and the pungent chemicals of the now incessant baths which he insisted on taking unaided.[36] I perceived that it must be connected with his ailment, and shuddered when I reflected on what that ailment might be. Mrs. Herrero crossed herself when she looked at him, and gave him up unreservedly to me; not even letting her son Esteban continue to run errands for him. When I suggested other physicians, the sufferer would fly into as much of a rage as he seemed to dare to entertain. He evidently feared the physical effect of violent emotion, yet his will and driving force waxed rather than waned, and he refused to be confined to his bed. The lassitude of his earlier ill days gave place to a return of his fiery purpose, so that he seemed about to hurl defiance at the death-daemon[37] even as that ancient enemy seized him. The pretence of eating, always curiously like a formality with him, he virtually abandoned; and mental power alone appeared to keep him from total collapse.

The Best of H.P. Lovecraft

The Best of H.P. Lovecraft The Definitive H.P. Lovecraft: 67 Tales Of Horror In One Volume

The Definitive H.P. Lovecraft: 67 Tales Of Horror In One Volume The Complete Works of H.P. Lovecraft

The Complete Works of H.P. Lovecraft Other Gods and More Unearthly Tales

Other Gods and More Unearthly Tales Lovecraft's Fiction Volume I, 1905-1925

Lovecraft's Fiction Volume I, 1905-1925 The Shadow Out of Time

The Shadow Out of Time The Shunned House

The Shunned House Lovecraft's Fiction Volume II, 1926-1928

Lovecraft's Fiction Volume II, 1926-1928 The Thing on the Doorstep and Other Weird Stories

The Thing on the Doorstep and Other Weird Stories Dream Cycle of H. P. Lovecraft: Dreams of Terror and Death

Dream Cycle of H. P. Lovecraft: Dreams of Terror and Death Great Tales of Horror

Great Tales of Horror Shadows of Death

Shadows of Death Delphi Complete Works of H. P. Lovecraft (Illustrated)

Delphi Complete Works of H. P. Lovecraft (Illustrated) Waking Up Screaming: Haunting Tales of Terror

Waking Up Screaming: Haunting Tales of Terror H.P. Lovecraft Goes to the Movies

H.P. Lovecraft Goes to the Movies The Road to Madness

The Road to Madness The Complete H.P. Lovecraft Reader (68 Stories)

The Complete H.P. Lovecraft Reader (68 Stories) The Horror in the Museum

The Horror in the Museum Collected Fiction Volume 1 (1905-1925): A Variorum Edition

Collected Fiction Volume 1 (1905-1925): A Variorum Edition Lovecrafts_Fiction, vol.I_1905-1925

Lovecrafts_Fiction, vol.I_1905-1925 Writings in the United Amateur, 1915-1922

Writings in the United Amateur, 1915-1922 H.P. Lovecraft: The Complete Works

H.P. Lovecraft: The Complete Works Collected Fiction Volume 3 (1931-1936): A Variorum Edition

Collected Fiction Volume 3 (1931-1936): A Variorum Edition H.P. Lovecraft: The Complete Fiction

H.P. Lovecraft: The Complete Fiction Collected Fiction Volume 2 (1926-1930): A Variorum Edition

Collected Fiction Volume 2 (1926-1930): A Variorum Edition Yog Sothothery - The Definitive H.P. Lovecraft Anthology

Yog Sothothery - The Definitive H.P. Lovecraft Anthology The Complete H.P. Lovecraft Collection (Xist Classics)

The Complete H.P. Lovecraft Collection (Xist Classics) The Watchers Out of Time

The Watchers Out of Time Eldritch Tales

Eldritch Tales The Other Gods And More Unearthly Tales

The Other Gods And More Unearthly Tales The New Annotated H. P. Lovecraft

The New Annotated H. P. Lovecraft At the mountains of madness

At the mountains of madness Bloodcurdling Tales of Horror and the Macabre

Bloodcurdling Tales of Horror and the Macabre Fossil Lake II: The Refossiling

Fossil Lake II: The Refossiling Shadows of Carcosa: Tales of Cosmic Horror by Lovecraft, Chambers, Machen, Poe, and Other Masters of the Weird

Shadows of Carcosa: Tales of Cosmic Horror by Lovecraft, Chambers, Machen, Poe, and Other Masters of the Weird H. P. Lovecraft

H. P. Lovecraft The Cthulhu Mythos Megapack

The Cthulhu Mythos Megapack The Complete H. P. Lovecraft Reader (2nd Edition)

The Complete H. P. Lovecraft Reader (2nd Edition) The Complete Fiction

The Complete Fiction Waking Up Screaming

Waking Up Screaming Transition of H. P. Lovecraft

Transition of H. P. Lovecraft![[1935] The Shadow Out of Time Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/12/1935_the_shadow_out_of_time_preview.jpg) [1935] The Shadow Out of Time

[1935] The Shadow Out of Time The Horror Megapack

The Horror Megapack